“It was meaningful, because Christie would not connect with an unknown and untalented watchmaker, knowing her and how meticulous and exact she is,” Ulm had deduced in the stately setting where such masterpieces as Dead Man’s Folly and Five Little Pigs had taken seed. Inspired to solve another mystery from the arch crime writer’s cannon — the case of the vanished 18th century Genevan horologer — “I thought there must be something special here, and I was right.”

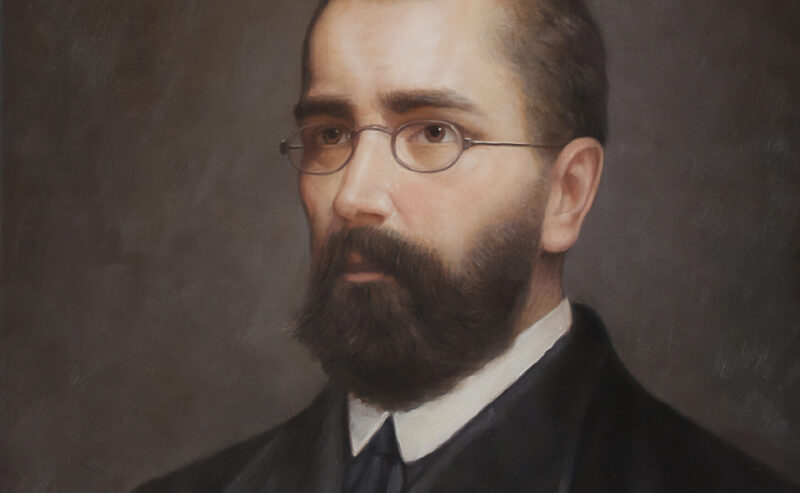

“Instinct is a marvellous thing, it can neither be explained nor ignored,” to quote the words of Christie herself. Monsieur Ulm’s Europe-wide hunt led him from Greenway to Paris’ Petit Palais, where an exquisite, gold signed renaissance-style pocket watch was displayed, a secret society of worldwide collectors from whom the financier sourced several antique pieces at auction and here, at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire à Genève. The horologer had been unmasked as Charles Girardier masquerading under the pseudonym ‘Girardier L’Ainé.’